Even among hard-core "fine art" photographers Edward Weston's name isn't much mentioned any more.

Weston never received the popular acclaim, much less the financial rewards, Ansel Adams [if you really need a link or a wiki to find out who Ansel Adams was, please immediately dig a hole in your backyard and plant your camera in it] enjoyed during his life, which is a pity, considering that Weston's pioneering contributions helped establish photography as "art," an accomplishment largely responsible for painters like Picasso shifting from realism toward abstraction ... which in turn might be part of the reason so much digital photography is not only dreadfully bad, but artistically unforgiveable.

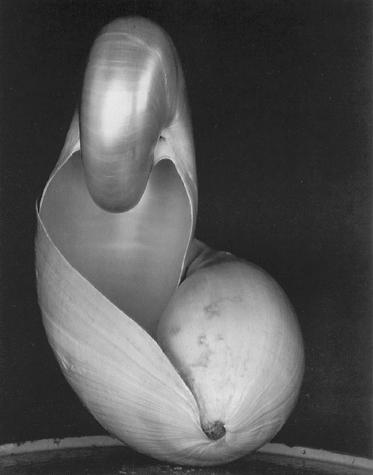

Between the 1920s and late 1940s Weston struggled with his old camera, literally, to find "the essence behind the thing," often staring at his subjects ... peppers, seashells and onions ... for days at a time without exposing a single negative.

Not until he "felt" the thing behind the image.

Then he'd load his rickety view camera with a wood film holder, expose the negative always always always at f/64 and develop the film by hand in a tray, before finally printing an 8x10" contact print (again by by hand) in an extremely toxic Amidol solution from the original 8x10" negative.

Then Weston began fine-tuning each successive print, until finally arriving at a representation of "the thing" his mind had pictured. Sometimes it took dozens of sheets of papers to get the image "right."

That's hardly the approach photographers embrace today as prétendants seek out the latest, smallest digital cameras packed with the latest technology promising the most mindless, attention-free operation, conveniences which supposedly leave the photographer with nothing more encumbering than pressing the shutter button 30 or 40 times to "inhibit his creativity"... probably the most popular excuse yet for laziness. But digital chips calculating auto-focus and auto-exposure count for nothing more than a digital dispensation for inexperience, immaturity and artistic crudeness.

If you're a photographer, The f-stops Here.

Unless my memory fails me (not unusual), "Two Nautilus Shells" (above) required a 4-hour f/64 exposure. That means Weston could only try once a day to get the image "right" before the light faded, and the sheet film was ruined.

Weston lived in an unheated shack with neither electricity or plumbing, and was known to skip meals to buy the film, chemicals and paper he needed instead.

In his journal Weston describes pushing hunger from his mind as he counted off the hours necessary to expose his last sheet of film, film he'd purchased with his entire weekly food allowance, watching the clock tick slowly past three hours and then crossing his fingers that this negative would be the one ... only to have the vibration from a passing truck cause the shells to topple over, ruining his exposure, leaving him with no film, no money, and no food for the rest of the week.

Bruce Barnbaum recently told me, "Every year more students show up for workshops with digital prints, always excited to tell me how digital photography has made their work so much easier and faster. But none of them tell me how digital photography has made their easier faster pictures better."

John Sexton (who was Ansel Adams's last assistant) told me, "A lot of people want to do the least work they can, and get famous with their cameras." A workprint Sally Mann sent me (her letter was written on the back) again showed me there is no substitute for craft.

Here in The Age of The Cutting Edge, no wonder Weston's diligence and devotion to craft is so easily neglected and dismissed. We don't have time to learn that stuff: THOUGHT-FREE OPERATION helps us hide behind the argument I know what I like because I like it (whether it's any good or not).

The translation is I know what I like when I like it, and don't care about learning anything else.

That's why we see techheads with "shooting vests" and titanium tripods blazing away with the shutter in machinegun mode, crossing their fingers they'll luck-out with an "interesting image." They want to lead the cutting edge, without bothering to learn the first thing about the basic craft of what they're doing.

I see too many photographers today who'd be embarrassed, or even angry, to admit they can't even describe the emotion behind their own work (though they've got the latest gear) ... yet they don't have enough interest or they're too busy to learn the difference between The Zone System and a flash slave.

It shows in their work.

Those are the photographers who're only excited about what's caught their attention for that moment,and once they're done numbing their fingers from squeezing the shutter, they're ready to move on to whatever luck hands them next.

Thanks for your picture, please pull around and have your next image ready at the next window.

No comments:

Post a Comment